When it comes to curbing delinquent behavior in teenagers, a label or diagnosis does not really matter; it is not what will make a child stop drinking, fighting, or engaging in other harmful behaviors. What matters most is what will make the behaviors stop. And according to Patrick Duffy Jr., PsyD, author of Parenting Your Delinquent, Defiant, or Out of Control Teen, finding a solution requires identifying all the areas of your child’s environment that may be producing his bad behavior.

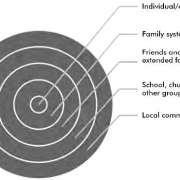

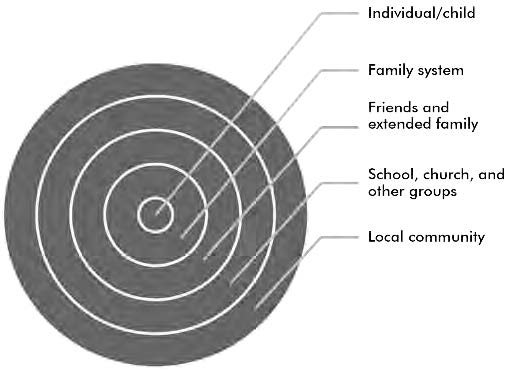

We can probably all agree that a child’s behavior is influenced by other people. Decades of study have told us that a juvenile’s behavior is determined by multiple influences from the environment, including the family, the peer group, the school, the neighborhood, and the broader community (Huizinga, Loeber, and Thornberry 1995).

It is important to understand that all the areas listed above affect one another, and tend to work in predictable sequences or patterns. Just as a car has many parts, or systems, which must work well together, your child’s environment is made up of many parts, or systems, that work to produce or allow a particular pattern of behavior. Each of these systems has an influence over a teen’s behavior. They also influence each other. For example, if a child exhibits threatening behavior toward a parent and is given what he wants as a result, he is likely to use the same behavior to get his way the next time. The parent has essentially rewarded him for the threatening behavior. In this way, the parent’s behavior increases the child’s threatening behavior. This is known as “reinforcing,” which means increasing the likelihood of a behavior by responding to it in a manner pleasurable to the child.

The child’s behavior has also had an effect on the parent’s behavior. The threatening behavior has made it less likely that the next time the parent will hold firm and not give in to the child. And when the child stops threatening after the parent acquiesces, it reinforces that behavior in the parent. As a result, these two systems are engaged in a predictable sequence: The parent initially tells the child no. The child predictably becomes aggressive, and the parent gives in to the child’s demands, increasing the likelihood that the child will be aggressive next time. This is one example of how systems interact to maintain a child’s behavior.

Let’s say there are behavior problems at school. If the family is not aware of the behavior, the separate systems of the school and the family will not work together to change the behavior. Also, if the two systems, family and school, argue over who is to blame, interaction between the two sides may decrease, making it more likely that the child’s behavior will continue while the two sides debate. However, if they are in frequent contact and work well together, they will be much more likely to be successful in altering the behavior. They may develop a strategy where school personnel report the child’s behavior to the parents, who respond with praise or punishment based on the behavior. This coordinated effort is more effective than the two systems operating independently and without knowledge of each other’s efforts.

The image to the right (based on Bronfenbrenner, U. 1979, 1988) represents the major systems influencing your child’s behavior. These systems are arranged in order of proximity, starting with those closest to your teen, which have the most direct influence. As the diagram shows, the family has the most influence. For this reason, it is most effective to begin with the family and surrounding environment. The most effective approaches use the family as a starting point to spark change in the other systems such as school, peers, and neighborhood. By altering the systems and influences on your teen’s behavior, you can effectively change his behavior, too.

Next week we’ll take a closer look at some of the specific targets for intervention within the spheres of family, peers, and school. For more information, check out Duffy’s new book, Parenting Your Delinquent, Defiant, or Out-of-Control Teen: How to Help Your Teen Stay in School and Out of Trouble Using an Innovative Multisystemic Approach.

References

Huizinga, D., R. Loeber, and T. P. Thornberry. 1995. Recent Findings from the Program of Research on the Causes and Correlates of Delinquency. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Bronfenbrenner, U. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U. 1988. “Foreword.” In Ecological Research with Children and Families: From Concepts to Methodology, edited by A. R. Pence. New York: Teachers College Press.

2024 Peace Playbook: 3 Tactics to Avoid Clashes with Your Partner

2024 Peace Playbook: 3 Tactics to Avoid Clashes with Your Partner