Whether you are a novice or advanced practitioner in acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), you know that metaphors and exercises play a crucial role in its successful delivery. These powerful tools go far in helping clients connect with their values, and give them the motivation needed to make a real, conscious commitment to change.

Relational frame theory, (RFT) supports the use of metaphor in therapy by suggesting that the unique capability of humans to respond to derived relationships is exactly what traps us in emotional suffering. Specifically, our abilities to plan, predict, evaluate, verbally communicate, and relate events and stimuli to one another both help and hurt us (Hayes et al., 1999). Our higher cognitive abilities allow us to solve problems, but we often wrongfully apply these same skills to our inner experiences. We believe we should be able to control the way we think and feel in the same way we can control our hair or our houses.

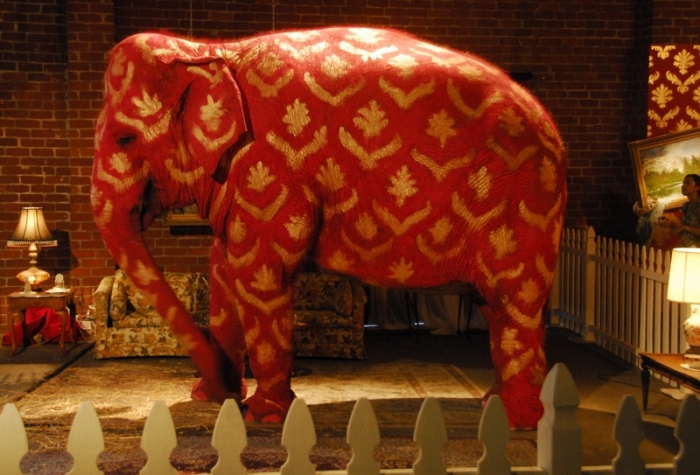

Mounting research demonstrates that the more we attempt to suppress the thoughts and feelings, the more present they become (Abramowitz, Tolin, & Street, 2001; Campbell-Sills, Barlow, Brown, & Hofmann, 2006). In addition, although these attempts to avoid our internal experiences (i.e., experiential avoidance) may appear to work in the short term, they ultimately lead to a more restricted existence. For example, a person who feels anxiety every time he enters a social situation may temporarily reduce his anxiety by avoiding interpersonal encounters; however, his ability to live life freely will become greatly limited, and his fear of social interactions will persist. So the verbal rules we successfully use to solve many problems in the external world typically cause suffering when we attempt to use them to “solve” painful thoughts and feelings.

ACT stipulates that overidentification with literal language leads to psychological inflexibility, and that this inflexibility is at the core of human suffering. This interrelationship can be further broken down into six core pathological processes: experiential avoidance, cognitive fusion, dominance of the conceptualized past and feared future, attachment to a conceptualized self, lack of clarity regarding values, and lack of actions directed toward values. The ACT path to emotional well-being involves moving toward psychological flexibility via six dialectical therapeutic processes.

When confronted with the tricks that language plays on people who suffer from psychological difficulties (and people in general, ourselves included), therapists need to reconnect clients to useful elements of their experience. In psychotherapy, this can be done without language, since almost everything that happens in a therapy session is the result of symbolic interactions (that is, even a moment of silence means something). Thus, therapists need to use language in an experiential way, and this is the path chosen by ACT and other third-wave psychotherapies, such as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), and functional analytic psychotherapy (FAP).

In the coming weeks we’ll take a closer look at some of the experiential techniques that can be used throughout the course of ACT, as well as ways to use language and metaphor to achieve favorable outcomes. For more on the use of metaphors in ACT specifically, check out The Big Book of ACT Metaphors.

References

Abramowitz, J. S., Tolin, D. F., & Street, G. P. (2001). Paradoxical effects of thought suppression: A meta-analysis of controlled studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 21, 683–703. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(00)00057-X.

Campbell-Sills, L., Barlow, D. H., Brown, T. A., & Hofmann, S. G. (2006). Effects of suppression and acceptance on emotional responses of individuals with anxiety and mood disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 1251–1263. doi:10.1016/j. brat.2005.10.001.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. New York: Guilford Press.

2024 Peace Playbook: 3 Tactics to Avoid Clashes with Your Partner

2024 Peace Playbook: 3 Tactics to Avoid Clashes with Your Partner