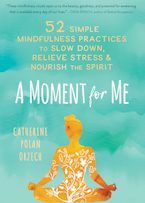

By Catherine Polan Orzech, MA, LMFT, author of A Moment for Me

One of my favorite Pixar movies is Inside Out. It’s a narrative representation of the human mind, and the central characters are a few core human emotions—Joy, Sadness, Fear, Anger, and Disgust. We learn about how they function inside the mind of a twelve-year-old girl. Two of the main characters, Joy and Sadness, seem like ill-matched roommates. They are housed within the same mind and need to figure out a way to work together. Luckily, they do and in so doing, they learn a great deal about the benefits that each brings to the richness of life.

Joy and grief, pain and pleasure: just as we know light because of dark, we only know one because of the other. We are guaran-teed to experience each of these in the course of our lives and many in the course of one day. Our tendency is to strive for one and push away the other. But what if we too could allow them to harmoniously coexist?

In this very moment, these polar-opposite expressions of our humanness do coexist. Try tuning in to your own body. Are there any areas of pressure, tightness, achiness, itchiness, or other kinds of mild-to-challenging discomfort? Usually we only have to sit still for a few moments for something of this nature to arise and make us want to move or shift to regain the elusive experience of being in a body without any unpleasantness. It may even be significant pain that is here right now. Whatever the degree of the discomfort, just acknowledge its presence as if you are compassionately attending to a dear friend who is in pain. Now, shift your attention to another place in your body where things feel just fine. Places I like to go for this are an earlobe, the skin on the back of my calf, or the inside of a forearm. But any place will do. There might be many places in the body that feel just fine right at this very moment, and these too—like the places of discomfort—are housed within you.

Find one area of discomfort and one area of pleasant or neutral sensation and try to hold them both in your mind at the same time. For many, doing this makes the “pain” less painful and more bearable because it is not alone in the body. It is being experienced as just one part of a larger, more varied whole.

Our pain or sadness can actually be an opportunity for us to open to reservoirs of joy and comfort that we have coexisting within us. Rather than our reactive bouncing between the poles of pain and pleasure, joy and sadness, our task is to become the expansive house of integration.

Open to All

It takes practice to learn how to let seeming opposites coexist within us. Try this practice to learn more about what is within you whenever you experience physical or emotional discomfort. When you experience a moment of discomfort, physical or emotional, first gently turn toward how it feels in the body.

Take note of the kind of physical sensations you experience rather than just identifying the overall experience as “pain,” “sadness,” or some other word. See if you can describe what it actually feels like—tight, achy, pressure, and so on.

Now, expand your awareness of your body to other neutral or pleasant sensations that are part of the present moment.

Remind yourself that these too are alive within you.

Allow both to be held in your awareness simultaneously.

Sitting Here in Limbo

Have you ever been in limbo—in that liminal space where something has just finished but something else has not yet begun? Perhaps a relationship, a job, even a favorite Netflix series has ended. When this happens, we feel unmoored and cast out to sea. Our boat is on its way somewhere, but the destination feels distant and we can’t quite see it.

None of us really likes the great unknown! In fact, simply admitting we don’t know makes us feel anxious. That’s not personal. Our minds are conditioned to fill in the blanks with all sorts of ideas, stories, and assumptions when we face uncertainties, either intense or mundane.

However, have you noticed that the mind doesn’t usually come up with all sorts of amazing possible—and positive—scenarios? Nope. Ever the lover of drama, the mind usually prefers to fashion the worst outcomes—especially if we’re already anxious or challenged in some way. Our current mood, whatever it is, will influence the way in which we perceive, experience, and think about what happens next. And have you ever noticed that these future catastrophes rarely happen? But when we are depleted in some way, we will alter the trajectory of the story we tell ourselves in a negative way. And we are much more vulnerable then to believing our thoughts.

Go Beyond

The Indian saint Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj gives us this instruction for these “in-between” spaces: “Whatever you come across, go beyond.” I believe he is inviting us not to take all our assumptions and stories about the future at face value. We need to see beyond the conditioned activity of the mind in the face of the unknown. We can go beyond the stories we tell ourselves and see a larger picture, which will ground us.

Can you notice the difference between how you perceive the bare facts of the situation and how you perceive that same situation when you add your interpretations of it? The next time you encounter an ambiguous moment—for instance, when you hear a tonal shift in the voice of someone you care about—watch your mind and see what it is telling you. What conclusions is it making up about why that person changed their tone of voice?

Understanding How We Build Stories

This week, begin to notice how your mind “adds on” extra narratives and conclusions about what is actually happening.

Before you share your thoughts, beliefs, or assumptions about a situation, preface your statement with “The story I’m telling myself is…” This will help you become aware that a story is being told and that underneath the story is a moment of “not knowing.”

Use the mantra “thoughts are not facts” to remind yourself that just because you think something doesn’t automatically mean it is true.

Breathing In, Breathing Out

Did you ever stop and consider that the breath you are breathing is actually an exchange?

Everything is in a process of exchange—of coming and going—and this body of ours is just the permeable envelope through which these exchanges occur.

When we breathe in, we experience an expanding and filling from the chest to the abdomen, and even into the back. If we pay attention, we can also experience a kind of tickling in the nostrils as the air rushes past and enters the body. And as you breathe out, the reverse happens. The breath is released as the chest cavity gets a bit smaller, which causes the lungs to deflate and the breath to move back out of the nose.

It can be incredible to remember that this one breath, the one that is happening right now, contains oxygen that has been created in cooperation with the trees as well as other gases that are part of our atmosphere. We draw in a breath and the body goes to work absorbing the oxygen into the bloodstream so that it can nourish all of the cells of our bodies. When we breathe out, carbon dioxide is offered back into the atmosphere. It is then picked up by the trees, because carbon dioxide is what they need in order to create oxygen. Each breath is a direct experience of our interconnectedness—and not just interconnectedness with the trees but with all living breathing things. There is no such thing as my breath. But it is the breath that takes its turn uniting and intermingling with all life.

The breath is a friend—and also a teacher. It always teaches us how we can receive and also how to let go. It is here, and then it is gone—just like everything else we can experience in a moment. By paying attention to the breath in this way, we also gain skill at paying attention to other body sensations, to sounds, and even to thoughts. Just like the breath, they are all impermanent. We can no more own a sound than we can a breath or even a thought. They are not mine, but are simply the phenomena making up what we call this moment.

Breath and Mind

Take a moment to notice that the breath and the thinking mind are intimately linked. The breath is linked to how active the mind can be, as well as to the autonomic nervous system that regulates both the fight-or-flight response and the relaxation response. When the breath is relaxed, even, and steady, the mind tends to follow. When we are stressed and the fight-or-flight response is active, the breath tends to be rapid and shallow. If we continue breathing rapidly, the body still thinks it’s under threat and will keep the fight-or-flight system going. In contrast, notice what happens when you start to take some deep breaths. The stress response system begins to subside and turn itself down. The breath can act like a dial, either turning up the volume of the stress response when it is rapid and shallow or turning it down when it is slow and steady.

You don’t even have to consciously slow down the breath. Simply bringing a kind and curious attention to it tends to slow it down and allow it to regulate all on its own. So, pay close attention to what actually happens as you breathe. Taste the breath, savor it, feel its rhythmic flow happening in and through you. Then, see what happens when you move your attention to sounds and then to thoughts. See if you can observe these other sensory experiences with the same kind and curious attention.

Awareness of Breath

This week, notice the activity of your breath and the activity of your mind.

Be aware of what you are taking in—through your breath and in your body, mind, and emotions. What we take in becomes a part of us and then is offered back out. What we take in is what we digest and then release.

When you breathe in, try to connect that process with some intention for your well-being. For instance, imagine placing the wish for ease or safety or love right on your in-breath. Let your body soak it in and be nourished by it.

Then, as you breathe out, imagine that same wish flowing out of you and being offered to someone you care about or to the person walking near you, because it’s likely that they have the same need for ease and peace as you do.

Feel how your breath connects you with nature itself as you exchange oxygen and carbon dioxide, which both you and nature need to thrive and survive.

Catherine Polan Orzech, MA, LMFT, has taught mindfulness for over two decades. She is certified mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and mindful self-compassion (MSC) teacher; and is currently faculty in the departments of psychiatry, and obstetrics and gynecology, at Oregon Health & Science University, where she’s involved in research on mindfulness and women’s health.

2024 Peace Playbook: 3 Tactics to Avoid Clashes with Your Partner

2024 Peace Playbook: 3 Tactics to Avoid Clashes with Your Partner